A favorite book of intellectual conservatives is “Ideas Have Consequences,” by Richard Weaver, a University of Chicago academic who dug deep into a lost intellectual culture of his native South. In another book, “The Southern Tradition at Bay,” he unearthed a supposed alternative (Southern, without dwelling on the problem of slavery) to America’s soul-enfeebling forces of industrialism, capitalism and individualism. “Ideas Have Consequences” is more philosophical, an attack on the materialism, positivism and empiricism underpinning modern science and technology. It’s an appealing notion, but too abstract as an account of our complicated world today, or of human nature.

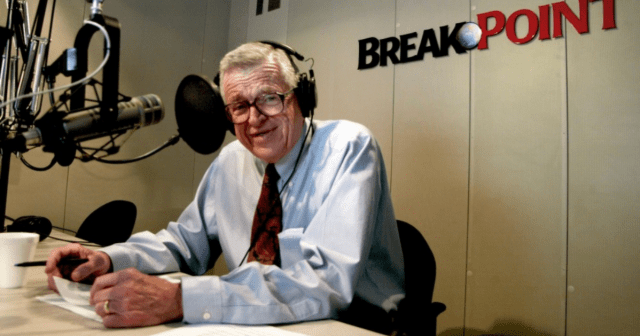

But some ideas do seem to have specific consequences, especially bad ideas that are packaged like candy-colored pills in a word or phrase. One of these is the idea of a “Christian worldview.” One dark and lonely night when I was driving home to the Shenandoah Valley from a Richmond hospital, I heard this phrase on a talk-radio show. My feelings were in a heightened state, alert to reality and divine presence as our daughter lay in that hospital recovering from bone-cancer surgery. Callers to this radio show, called “BreakPoint,” were complaining about various ways that schools were pushing godless and anti-Christian positions in American classrooms. Their generalizations bothered me, and much of their evidence seemed paranoid or flatout wrong. I had covered these sorts of classroom controversies as an education reporter. What bothered me more than the callers was the way the host accepted their stories uncritically, and then elevated them into his unifying idea that he called “a Christian worldview.”

The host, I learned during a program break, was Chuck Colson. Really? The lying SOB legal counsel of Nixon’s White House during that moral collapse in high places known as Watergate? Yes, that Chuck Colson. I knew of his born-again conversion to Christianity, because I had heard him about 30 years earlier explaining at the Atlanta Press Club how he had arrayed the arguments of C.S. Lewis’s “Mere Christianity” on a legal pad, countered these with lawyer-like objections, and judged that his emotional conversion experience, on balance, was also intellectually valid. I’m a C.S. Lewis fan, so I identified with his thought process. Thirty years later, I knew that Colson’s time in prison had led him to start a Prison Fellowship that he saw grow into a national program that was doing good for a lot of inmates. This was real Jesus work, I was sure. “I was in prison, and you visited me.”

But listening to him spin out the resentments inherent in the concept of a “Christian worldview” angered me. I resolved to check out the callers’ assertions that he was accepting, and exploiting. “If your mother says she loves you, check it out,” we like to joke about how journalists think. My doubts, later, checked out.

Colson died in 2012. His funeral in the National Cathedral honored, as it should, his good work through Prison Fellowship and his influence on George W. Bush’s remarkably sweeping fight against AIDS and HIV in Africa.

He was also responsible for pushing the notion of a “Christian worldview,” an idea that has had consequences. You can see it in our political divisions today, in the way entire churches of evangelical Christians can turn out any pastor they perceive as a “liberal.” Not that these “Christian worldview” folks follow the difficult Amish-style Christian tradition of “be ye separate” by actually leaving the culture of cars, TV, suburban enclaves, voting and shopping malls (unless it’s in a survivalist, militia-forming unit). Instead, there is now a subculture and mindset that fears what’s beyond their Christian bookstore readings, prescribed enjoyments and politics. Out there is another “worldview” that is unbiblical and lacking in moral absolutes.

“Chuck became convinced that it was absolutely necessary to develop a Christian worldview—a comprehensive framework regarding every aspect of life, from science to literature to film to politics,” wrote Eric Metaxas in “Seven Men: And the Secret of Their Greatness.” Metaxas is a best-selling biographer pushing ideas that seem to come out of his assumption of “a Christian worldview.” So he interprets facts from this perspective. He says that Colson knew that the “real” cause of crime is not poverty or “race,” but a lack of moral training. He says Colson knew this by studying the writings of sociologist James Q. Wilson. I’ve read Wilson’s “Thinking About Crime” and took the course, “Crime and Human Nature,” that his collaborator Richard Herrnstein taught at Harvard when their book of that title came out. It’s true that these conservative scholars question environmental factors like racism and poverty as the primary causes of crime, but what they find instead is inherent factors like an individual’s impulse control, time-horizon and perceived consequences. These are behaviorist factors, not something from Colson’s ideology of moral decline.

Is it possible for Chuck Colson to be an authentic born-again convert and powerful witness for prisoners and prison-reform but also be wrong about “a Christian worldview”? Is it possible that the way Christians live in both the City of God and the worldly city has always been complicated, at least since St. Augustine’s day as Christians assumed civic responsibility in the decline of the Roman Empire? The Enlightenment ideas of liberal democracy, checks and balances, regulated free enterprise and equitable laws have been remarkably good for the country, and for communities of faith. Another good idea in that cluster of 18th century ideas is religious tolerance – the twin balance of the First Amendment, freedom of religious expression (the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1890s said that was only about opinions, not actions, and Justice Scalia oddly enough rolled back religious rights to that dry notion in 1990, prompting a huge bipartisan reaction called RFRA) but also freedom from religious establishment (e.g. prayer in public schools). We live in a pluralistic, multicultural society, thanks to these old time-tested ideas. Many forces of the 21st century are undoing trust in these liberal, democratic ideas and institutions, on the left and right. Colson’s idea of a “Christian worldview” was an early antagonist for eroding that trust.