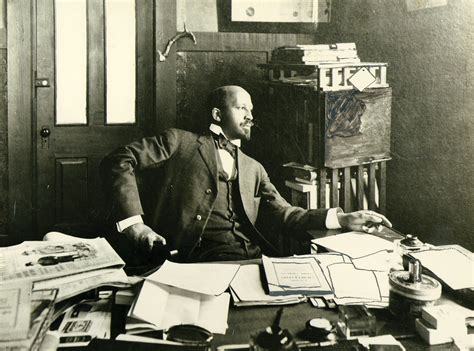

In a 1963 issue of the Atlantic Monthly, I read an account by Ralph McGill, who was editor and publisher of the Atlanta Constitution when I was growing up in Atlanta, of his interview with the distinguished black scholar W.E.B. DuBois in Accra, Ghana. DuBois was 94 at the time, and would die later that year, a disillusioned but dignified exile who had renounced his American citizenship and turned African Communist.

DuBois told McGill of his early days as a sociology professor at Atlanta University in the 1890s. One day in April 1899, DuBois was walking to the Constitution office with a letter of introduction to Joel Chandler Harris, an editor there at the time. But then he saw something in a store-front window that sickened him: the severed fingers of a man who had just been lynched. “I saw those fingers . . . I didn’t go to see Joel Harris and present my letter,” he told McGill. “I never went!”

It’s a famous scene in DuBois’s life, possibly a turning point as his literary and academic gifts became increasingly edged with resentment, with distrust of white society and a marathon determination to fight. This was four years after Booker T. Washington had famously held up his hands in a historic speech in Piedmont Park (as the Cotton States Exposition site would become), spreading his fingers apart as a metaphor for social segregation (which he conceded as a peace offering to the white South) on the metaphorical hand of “mutual progress.” DuBois respected Washington, but hated that “Atlanta Compromise.”

The fingers DuBois saw in the shop window were souvenirs of a lynching outside Newnan, in Coweta County. The case of Sam Hose, a black farmhand who had killed his white boss with an ax, had already received a great deal of coverage from the Constitution before Hose was lynched in broad daylight on April 23, 1899, before a crowd of perhaps as many as 2,000 jubilant citizens. The reason DuBois was going to see Joel Chandler Harris was to complain about the incendiary coverage the newspaper gave to the 10-day manhunt. The Constitution had offered a $500 reward, and published a description of the crime by the victim’s brother-in-law.

Fifteen years ago, I reviewed a research paper that a student wrote about the Constitution’s role in the Sam Hose case. “The South’s Standard Newspaper,” a century before I worked there in the 1990s, had adopted the style of sensational crime coverage so popular in the New York World and New York Journal. So the newspaper published the brother-in-law’s description of Sam Hose splitting his victim’s skull “to his eyes,” then knocking one of the children “six or eight feet,” dashing another, a baby, to the floor, and finally raping the wife “literally within arm-reach of where the brains were oozing from her husband’s head.”

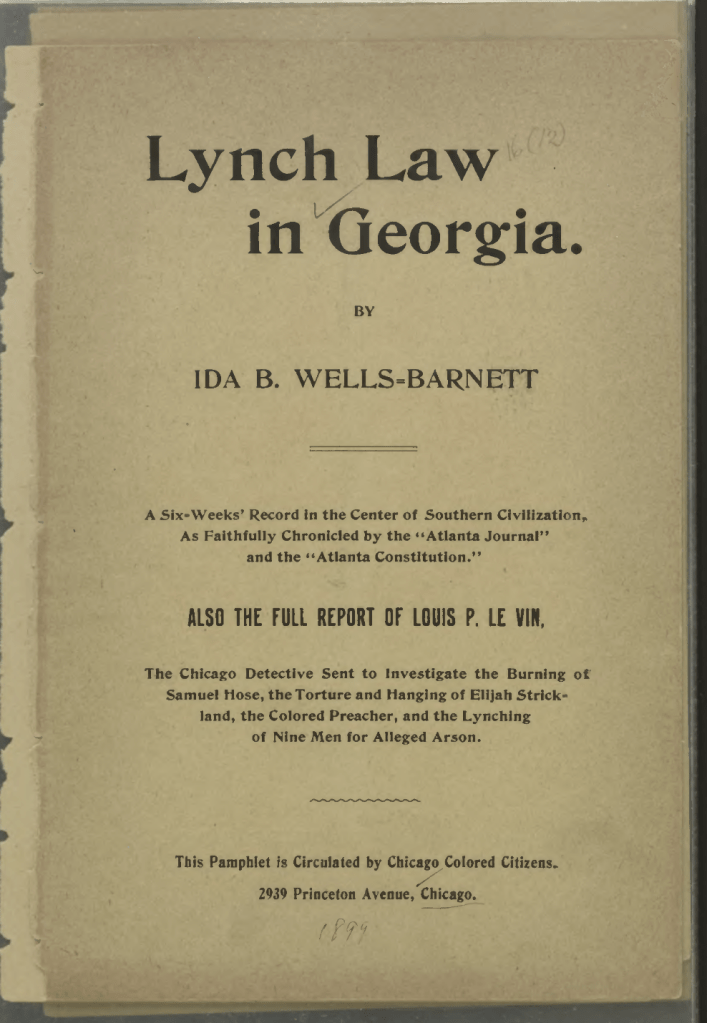

The brother-in-law was not present, and was not a trustworthy reporter. However, a muckraking black reporter named Ida B. Wells-Barnett, whose investigations of lynching around the South at this time proved to be highly credible, led a report on the case based on interviews of witnesses and other available evidence. The report, Lynch Law in Georgia, claimed that Sam Hose never entered the family’s home or touched the wife or children, but killed his boss, Alfred Cranford, in self-defense during an argument in which Cranford threatened him with a pistol. When he was finally captured and brought by train from Griffin, a terrified Sam Hose told a Constitution reporter the same version of events that Wells-Barnett would later publish. When the mob brought Hose before the wife’s mother, who asked him why he killed her son-in-law, he told her the same thing.

The excited throng offered to lynch the man right there in the older woman’s presence. She declined the offer. So they hauled him off to a clearing just north of Newnan, where he was chained to a pine sapling, stripped, and divested of several pieces of anatomy that were passed among the euphoric citizenry. A circle of firewood and this victim of Georgia’s extra-legal justice system were then doused with kerosene and lit a-fire. Hose’s only words during this final torture, according to the Constitution: “Oh my God! Oh, Jesus!”

It’s hard to imagine such community-wide, daylight savagery a mere four generations ago, looking at suburban Coweta County today. This was not some secret Klan activity, or the work of pathetic lowlifes, like the two Mississippi men who got away with Emmet Till’s murder in 1955. This was an entire community, like the town in Shirley Jackson’s gothic short story “The Lottery.”

Who stood up against it? Not the newspapers. Perhaps a case could be made that a few decent souls tried to stop the madness. Governor Allen D. Candler had dispatched the militia to Palmetto to try to prevent the lynching, though he had blamed black criminality as much as white vigilantism for Georgia’s epidemic of lynching. Former Governor William Y. Atkinson, a Newnan resident, had pleaded with the mob, ineffectively, to let the law take its course. These efforts remind me of how Governor John M. Slayton was moved by conscience to commute the execution of Leo Frank in 1915, though he could not stop Frank’s lynching in Cobb County in 1915. Weak leadership without followers. That’s what we had in Georgia in the worst of times.