How do you know . . . that South Korea had an authoritarian president named Yoon, and that Yoon declared martial law last December to shut down critics, an independent media and the National Assembly? Or that he was ousted by a snap election, and now faces criminal charges for leading an insurrection?

How do you know South Korea even exists?

How do I know that a South Korean family of three will be sending their first month’s rent for our furnished condo while my wife and I begin 12 months away? And that they will arrive soon, on a certain date?

The answer to the question “How do you know?” is always this: Trust.

I trusted the New York Times, AP, NPR, and in time, Wikipedia, to tell me the news about Yoon. I know the difference between trust-worthy news and trust-worthy opinion – such as the opinion of anti-Trump writers that South Korea’s ousting of Yoon is a good sign that democracy can win over authoritarian strongmen. That’s just an opinion, but at least it’s based on trust-worthy facts about what happened, and what’s happening.

I trust that South Korea exists, though I’ve never been to any Asian country. I was a questioning student, what they call a “critical thinker.” But the existence of South Korea cropped up in my schooling hundreds of times, from maybe 3rd grade and from my parent’s talking about the Korean War all the way to today. And there was never a suggestion – a conspiracy theory – that South Korea didn’t exist.

How do I know that our real estate agent found good tenants for our condo? It’s because of trust. I trust our real estate agent. I trust the confidential salary report from the man’s South Korean university, and the online conversion table from South Korean “Won” to U.S. dollars. And a hundred other tiny signs and signals. I see the peer-reviewed papers he’s written about de-carbonizing transportation through public policy. And it makes sense to me that Georgia Tech would be bringing him to Atlanta for a year-long research fellowship. My world makes sense to me, and I can act in that world, because of trust. I know that millions of people live in that world. Or used to.

Something has gone wrong. People have lost their trust in things they should trust (and correspondingly, they seem to trust things they shouldn’t, like the Truth Social posts of a TV-savvy president who says things like, “All planes will turn around and head home, while doing a friendly ‘Plane Wave’ to Iran”).

I don’t know what is happening to trust.

But I was wondering how it began in American history, and I happened upon an interesting beginning. It happened in 1690, with two events that occurred within four months of each other. Both involved a printing press – a key element of the trust that grew in the West out of Gutenberg’s machine – and both occurred in Boston.

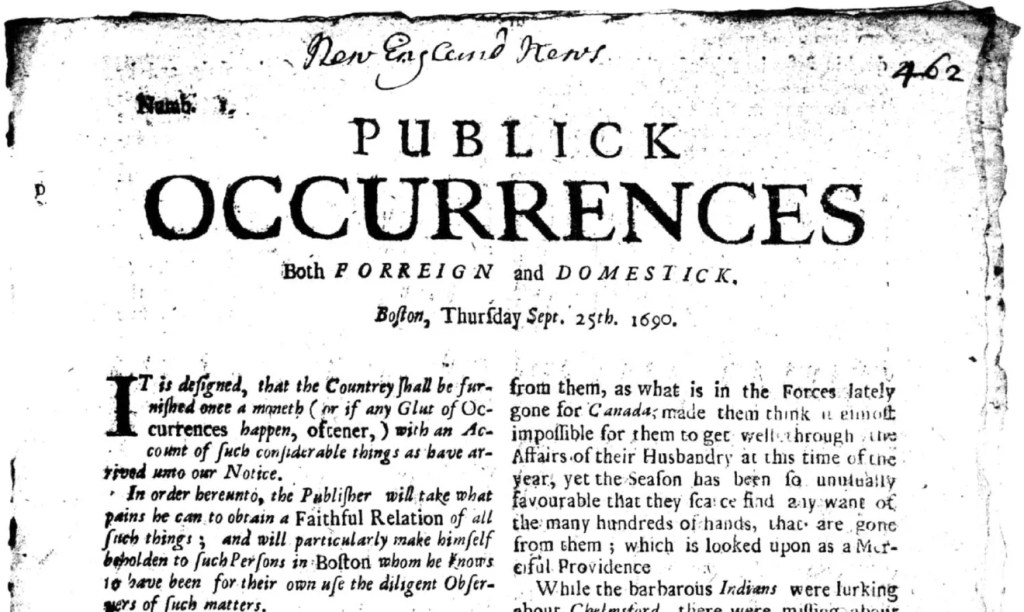

One was the printing of “Publick Occurrences, both Foreign and Domestic,” on September 25, 1690, America’s first newspaper. Benjamin Harris, a British scofflaw who had immigrated to the Puritan colony of Massachusetts, printed this newspaper without the government’s permission. The first issue, containing various interesting news reports, declared the newspaper had several goals. One was to see that people paid attention to “memorable Occurrences of Divine Providence,” the idea that God was blessing America not just through one’s own interpretation of the Bible but through its news and history, as difficult as those seemed – death, corruption, wars and all that. Also, to “cure or at least charm” the spirit of Lying that prevailed among people without a newspaper.

The king’s governor shut down Harris’s newspaper after that one issue. But others would come soon enough, like the New England Courant that James Franklin (Ben Franklin’s older brother who taught Ben printing) established in 1721, also in Boston.

The other “origin” of trust came on December 10, 1690, when the Massachusetts colony decided to print paper currency for the first time on America’s shores. The government created 7,000 pounds of “bills of credit” to pay militia who had attacked French soldier in Quebec City. The battle was a humiliating defeat for the attackers from Massachusetts, who were further humiliated by their colony having run out of money to pay them. As any economist can tell you, printing currency for the first time, with no gold or silver in the treasury to back it, was a doomed experiment. Wildly inflationary.

But in time, slowly, the idea of paper currency and credit grew. It grew on trust, “faith and credit,” a value agreed-on in common by people who enjoyed the benefits of such common trust. It took a long time, and it took a sense of honor, and self, and the common good.

Today, I can trust that the exchange rate between the South Korean Won and the U.S. dollar will hold steady. So will planning to rent an apartment in Italy with Euros. These are democracies with checks and balances, mixed economies, and a measure of trust in news, in the meaning of words, and in a pragmatic sense of how things are, really.

But there are curious signs and signals that this trust is breaking down.