Dan Wakefield, an American journalist, memoirist and novelist, died in Miami two days ago, March 13. I had met him when he came to speak to us Nieman fellows in 1986 or ’87. (Dan had been a Nieman Fellow 22 years earlier). Back then, he had just written a novel, “Selling Out,” inspired by his wacky experience in Hollywood writing the TV series “James at 15”). At Washington & Lee University, my colleague Kevin Finch encouraged me to get in touch with Dan, who was a friend of Kevin’s. On Oct. 31, 2018, he “visited,” by speaker phone, my class on “Civil Rights and the Press.”

From 1955-1960, Wakefield covered dramatic events around race and civil rights in the Deep South for The Nation. His articles from this period include “Justice in Sumner,” on the Emmett Till murder trial (September 1955), ‘Respectable Racism,” on the white Citizens Council movement (October 1955) and “Eye of the Storm,” on developments in the wake of the sit-in movement (May 1960). All three articles are included in the Library of America anthology, Reporting Civil Rights.

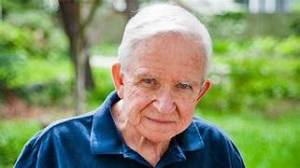

Wakefield led a charmed writer’s life, as one of Kurt Vonnegut’s best friends — both started writing for the student paper at Shortridge High in Indianapolis — and an observer of American life from the most interesting corners. When we talked to him, he was doing weekly readings in Indianapolis in a duet, “Uncle Dan and Sophie Jam,” with a young female saxophone player. At 86, he was funny, in full command of his storytelling gift, and generous with his time.

Here is a transcript of that interview. I hope you find it worth reading this entire transcript.

Prof. Doug Cumming: This is partly a demonstration of how to interview because these are freshmen, not necessarily journalism majors, though I’m in the journalism department. I’ve given them assignments to do at least one interview for a story or an oral history. And also, this is a class on the civil rights movement and the press, and I think we were all very impressed with the three articles we just read from your days with The Nation.

Dan Wakefield: Yeah. Thank you.

DC: As one of my students said, these are events that we’ve been studying – the Till trial, the white citizens council, and the sit-ins that began Feb. 1, 1960 – but we’ve never seen them written up with such flair.

DW: Yeah, well that’s great. You know one of the ironies to me, I’ve always said that the first sentence I wrote about the Till trial is the best sentence I ever wrote. I still think it is. And it’s too bad, because it was the first one I ever published. So all these years later I’ve never out-done it.

DC: Want me to read it out loud?

DW: Well, if you want to.

DC: “The crowds are gone and this Delta town is back to its silent, solid life that is based on cotton and the proposition that a whole race of men was created to pick it.”

DW: Yeah. I think that sums it up.

DC: The first question I want to ask you is to tell us about your creative life now, in what Walker Percy would call these latter days of the old USA.

DW: Well, I just finished writing a memoir of my goddaughter, who is a Cuban-American girl. I met her . . . I taught for 15 years at Florida International University in Miami, in the graduate writing program, and I met her family and I met her when she was 3 years old. And she’s now 23, and I just talked to her on the phone last night. And so that memoir has just gone out and is being considered, so I don’t know its fate yet. But I spent a lot of time on that. And then in recent years I’ve edited. . .first I was asked to edit and write an introduction to the letters of Kurt Vonnegut. He was a friend of mine and I’ve known his work well. We went to the same high school although 10 years apart, and then I edited a book of his graduation speeches, which are quite fun. And then just recently I co-edited a book of his complete short stories, which is 940 pages, and wrote an introduction to that. And I’ve also been doing some radio stuff. I did a thing on the local PBS station called “Uncle Dan’s Story Hour” and talked a lot about things I had written about and people I had met and so on.

DW: Well, I just finished writing a memoir of my goddaughter, who is a Cuban-American girl. I met her . . . I taught for 15 years at Florida International University in Miami, in the graduate writing program, and I met her family and I met her when she was 3 years old. And she’s now 23, and I just talked to her on the phone last night. And so that memoir has just gone out and is being considered, so I don’t know its fate yet. But I spent a lot of time on that. And then in recent years I’ve edited. . .first I was asked to edit and write an introduction to the letters of Kurt Vonnegut. He was a friend of mine and I’ve known his work well. We went to the same high school although 10 years apart, and then I edited a book of his graduation speeches, which are quite fun. And then just recently I co-edited a book of his complete short stories, which is 940 pages, and wrote an introduction to that. And I’ve also been doing some radio stuff. I did a thing on the local PBS station called “Uncle Dan’s Story Hour” and talked a lot about things I had written about and people I had met and so on.

DC: What is “Uncle Dan and Sophie Jam”?

DW: Oh that’s another show we do on Monday at a place call the Jazz Kitchen, it’s a nice dinner and jazz place in the city. When we did Uncle Dan’s Story Hour I had this wonderful young saxophone player, a young woman who had been playing here in town, and I liked her playing so much I added her to just play a song at the break of that hour-long show, and then at the end. So when that year was done I said, “You know, Sophie [Faught], I don’t want to have to talk another whole hour by myself so why don’t we do a show where you play for a half an hour, and you get some other musicians, and then I’ll talk for a half an hour, so that’s what that is. . . She started playing here when she was quite young at a place, and then she played with a lot of good musicians, she played in Carnegie Hall in New York and had a chance to be a jazz musician in New York but she preferred to come back here and to have children. She has one little girl and she’s about to have another in December.

DC: You’re still shopping your manuscript around about your goddaughter?

DW: Yes, it just went out about three weeks ago.

DC: What’s the title and what’s her name.

DW: Her name is Carina and the title is “Down by the Bay.” The title comes from, really, a kind of kindergarten song, “Down by the bay where the watermelons grow.”

DC: Let’s go back to the Fifties. . . .How did you get the job and how old were you when you started working for The Nation?

DW: It was really a fluke and I’ve always said to people, especially people starting out in some kind of writing effort, you have to be good and you have to be lucky. And I was really lucky because, well I had started out in high school. I was sports correspondent for the Indianapolis Star in high school, and I happen to know some of the sports writers and then one summer in college I worked on the sports desk of the Indianapolis Star and then another summer in college I wrote letters asking for a summer job at 40 different jobs in America and I only got one, and that was from the Grand Rapids Press in Michigan, and so I took that. And I was a general assignment reporter there. My first job after college was on a weekly paper in Princeton, N.J., and that happened to be the place where Murray Kempton, who was a well-known columnist for the New York Post, lived. And he had just had his first book out. And I reviewed his book. I was really a big fan of his work. I reviewed his book in the local paper. And he called me up and said, “Well you really [decked?] the book, come over and have a beer sometime.” So I said, “How about this afternoon?” and anyway, I got to know him, and he was like a mentor for me. And in the summer of ‘55, every newspaper in the country had headlines and stories about this Emmet Till case coming up in September in Mississippi.  And I said, oh my God if I could only get there and write about that. And so, just out of the blue, I called Murray Kempton and said, Is there any way, do you know any magazine that would let me write about that? And he said, “Well, The Nation asked me to write about it but I’m writing it for the New York Post, and I don’t like to write for two things at the same story, so I’ll tell them they should take you.” Well, I thought there’s not much chance of that. And I convinced him. I wished I had sometimes said what in the world did you tell them? Because the next thing I heard, he said, yeah, well go down to The Nation office and the managing editor will tell you what to do. And the managing editor. . .my payment for the story was a round-trip bus ticket from New York City to Sumner, Mississippi. That took about two days and one night. I stayed at a rooming house in Sumner, and covered the trial. And then, the trial was over Friday, and I was going to stay in the rooming house and write and Murray Kempton, who was there, said, no, it’s too dangerous. Come into Jackson. That’s where all the reporters are going to go. And I stayed in a motel in Jackson, Miss., over the weekend. I stayed up all night, and handed in this story Sunday morning. And you now, the way you filed stories in those days, you took it to the local Western Union office and they would send the story as a Western Union to the magazine. So that’s what I did, and I knew the story would appear on Monday, so I had to write it as if I’m looking back and the trial is over, which it was. So I just stayed up and did it. It was one of those events – it sort of had a form of its own. It started on Monday. It ended on Friday, and every day was very moving and very dramatic. You know, you just had to be alert and look at what was going on.

And I said, oh my God if I could only get there and write about that. And so, just out of the blue, I called Murray Kempton and said, Is there any way, do you know any magazine that would let me write about that? And he said, “Well, The Nation asked me to write about it but I’m writing it for the New York Post, and I don’t like to write for two things at the same story, so I’ll tell them they should take you.” Well, I thought there’s not much chance of that. And I convinced him. I wished I had sometimes said what in the world did you tell them? Because the next thing I heard, he said, yeah, well go down to The Nation office and the managing editor will tell you what to do. And the managing editor. . .my payment for the story was a round-trip bus ticket from New York City to Sumner, Mississippi. That took about two days and one night. I stayed at a rooming house in Sumner, and covered the trial. And then, the trial was over Friday, and I was going to stay in the rooming house and write and Murray Kempton, who was there, said, no, it’s too dangerous. Come into Jackson. That’s where all the reporters are going to go. And I stayed in a motel in Jackson, Miss., over the weekend. I stayed up all night, and handed in this story Sunday morning. And you now, the way you filed stories in those days, you took it to the local Western Union office and they would send the story as a Western Union to the magazine. So that’s what I did, and I knew the story would appear on Monday, so I had to write it as if I’m looking back and the trial is over, which it was. So I just stayed up and did it. It was one of those events – it sort of had a form of its own. It started on Monday. It ended on Friday, and every day was very moving and very dramatic. You know, you just had to be alert and look at what was going on.

I tell you, I was very naïve. I actually got there a day early and knocked on doors and said to people, “Hi, I’m from The Nation magazine in New York. What do you think about this trial?” It’s a wonder I didn’t get shot. But then I really almost got in trouble. . I’d heard that there was a witness. And I’d mentioned in the story a supposed witness named Leroy “Too-Tight” [Collins] being held in a jail, in a town called Itta Bena, and I’d heard that two of the sheriff’s deputies were going there, so I said, could I ride with them and they said, yeah sure, and I’d go about five miles out of town, they said, “Well, this is where you get off, boy.” And they let me off, and I walked back to Sumner. And Murray Kempton said, “You’re lucky all they did is leave you off.”

DC: A lot of pretty well-known reporters were covering the trial. Do you remember John Popham with the New York Times?

DW: Yes. There’s a picture of me with him in a book of mine called New York in the Fifties. There’s a picture of me and Murray Kempton, and we’re standing at the press table of the trial, John Popham is below us, and he’s writing something, and he has a hat in one hand, and has grey hair. So I met him, and the guys from the Detroit News. There was even a guy from Paris there, I believe. It was huge, you know, packed into that little courtroom. It was filled every day.

And the press table wasn’t really big enough for all the press.

DC: The writing reminds me a little of H.L. Mencken’s coverage of the trial in Dayton, Tenn., in 1925. You’re both coming in as outsiders, and poking fun a little bit but in a sensitive way. Who influenced your writing style at that time? Was it an editor at The Nation?

DW: No, not at all. At that point, I’d never met anybody at The Nation except the managing editor, who handed me the bus ticket. If anybody, it was Murray Kempton. You know, he later won the Pulitzer Prize when he worked for Newsday on Long Island. But he was a very revered journalist in New York City for many years. He wrote three times a week in the New York Post. I couldn’t wait to get it, everything he wrote. He was a great stylist.

DW: No, not at all. At that point, I’d never met anybody at The Nation except the managing editor, who handed me the bus ticket. If anybody, it was Murray Kempton. You know, he later won the Pulitzer Prize when he worked for Newsday on Long Island. But he was a very revered journalist in New York City for many years. He wrote three times a week in the New York Post. I couldn’t wait to get it, everything he wrote. He was a great stylist.

I think when I re-read the piece, I like the fact that it’s very direct. There’s nothing fancy about the style. It’s just trying to observe. I just re-read it this morning. And you notice that I talked about the color of Mose Wright’s suspenders and blue pants. All those things are obviously things you learn to do if you read good writing and read good journalism.

DC: Exactly. The details. So, Jack Eason of Bowling Green, Ky., who worked on his high school newspaper, has a question for you.

Jack: In your piece that we read, about the Citizens Council meeting in Montgomery, Alabama, you talked about how members of the Council, as you were leaving, tried to run after you and pull you from the car. Were there any other times when you were reporting on civil rights when you felt that you weren’t safe, or you were endangered?

DW: No. I think I was, in Sumner, Mississippi, when I was with those deputies, but I wasn’t aware of it until they had let me out of the car. No, that’s the only time. I tell you, it made a huge impression on me. Because when those guys started following me, I was at the meeting and then they were yelling at me, and I got in the car, and they were grabbing at me, it was the first time I felt, “Well, this is what it’s like when someone is attacking you as a symbol, you know? I remember when they said, “We know who you are,” I said, Well, I’d be glad to tell you and I turned around to shake hands, and they said, “No, no. We know.” They didn’t know anything about Dan Wakefield. They just knew I was a guy from New York who was writing about them and therefore I would be writing something not favorable. And I thought, well this is a tiny case, a very tiny sense of what it must be like to be a black person in this country, and somebody you know starts grabbing you, or attacking you, or beating you up or shooting you not because of the person you are, but because of what you stand for.

DC: Jack has a follow-up question.

Jack: You spoke a little to this, but could you describe more what their attitude toward northern reporters who were reporting on the civil rights movement was. . .Were they that hostile all the time, or was that an exception?

DW: It was always hostile, except one . . I will say, except one experience that struck me, I’ll never forget. I was interviewing a guy who was the head of the white Citizens Council, I think it was in Montgomery, Ala., and usually, you know, this was in the days before tape recorders. There were no tape recorders. You wrote everything down. So he’s talking and I’m writing. But what I do a lot of times is the guy says something really outrageous, I wouldn’t write right then. I would pretend I wasn’t writing and then later I would write it down when he started talking again, because I didn’t want him to realize I was writing down some terrible stuff. What he was saying to me. This guy was saying something about the goddam blacks, whatever, and I stopped writing, and he said, “Write that down, boy.” [laughs] “Okay.”

I remember he had this kind of jovial air about him. He said, “Well, you know, you and I don’t agree, it’s just like Macy’s talking to Gimbel’s.” Those were the two big department stores. They were rivals. His sense of his opinions and all the rest, he just saw it in some sort of joking way.

DC: You were in Montgomery just when the sit-ins began, we’ve read a lot about this. That was just when L.B. Sullivan, the police commissioner there, sued the New York Times in what became a landmark Supreme Court case. But you just happened to hear L.B. Sullivan addressing — I think it was — the white Citizens Council there. You were a lucky guy. The right place at the right time. Another question from Nick Mosher.

Nick: I was doing a little research on you and I saw that in college you became an atheist but then in 1980 on Christmas Eve in King’s Chapel you came back to being Christian. I was just wondering what was going on in your life or in the church on that night that caused you to change your belief system.

DW: When I went back to church at King’s Chapel on Christmas eve? Yeah well it was a lot of things that sort of come together that night. And I think part of it was, I went there because – and I think I described this in the book – but I went there because I realized I had lived in Boston for a long time but I really didn’t even know where any churches were. I just hadn’t noticed that, where the churches were, so I looked in the Boston Globe religion page and it said King’s Chapel – this was for Christmas Eve – candlelight service and carols. So I thought, well that will be innocuous enough, you know, that won’t be any big preaching or something that I won’t want to hear. So it didn’t say that the minister would read little things in between the hymns, and you know the passage from a novel by Evelyn Waugh that was about the mother of Constantine – I think the novel was called Helena – and there’s a beautiful passage toward the end of the book, and she says “Pray for the latecomers to the manger, and those who were not that aware for a while and came late.” So I felt like that was addressed to me. And it was very powerful. But also, I tell you, I go to a church where I am now, I think that nothing will ever compare to – in my eyes – what King’s Chapel in Boston was like in that era. I don’t know what it’s like now. And it was so powerful on Christmas Eve. People who usually didn’t go to church went there, the church was packed, and everybody got out the hymnal and it started out with everybody singing “Come All Ye Faithful, Adeste Fideles,” . . .and it was really very powerful.

DW: When I went back to church at King’s Chapel on Christmas eve? Yeah well it was a lot of things that sort of come together that night. And I think part of it was, I went there because – and I think I described this in the book – but I went there because I realized I had lived in Boston for a long time but I really didn’t even know where any churches were. I just hadn’t noticed that, where the churches were, so I looked in the Boston Globe religion page and it said King’s Chapel – this was for Christmas Eve – candlelight service and carols. So I thought, well that will be innocuous enough, you know, that won’t be any big preaching or something that I won’t want to hear. So it didn’t say that the minister would read little things in between the hymns, and you know the passage from a novel by Evelyn Waugh that was about the mother of Constantine – I think the novel was called Helena – and there’s a beautiful passage toward the end of the book, and she says “Pray for the latecomers to the manger, and those who were not that aware for a while and came late.” So I felt like that was addressed to me. And it was very powerful. But also, I tell you, I go to a church where I am now, I think that nothing will ever compare to – in my eyes – what King’s Chapel in Boston was like in that era. I don’t know what it’s like now. And it was so powerful on Christmas Eve. People who usually didn’t go to church went there, the church was packed, and everybody got out the hymnal and it started out with everybody singing “Come All Ye Faithful, Adeste Fideles,” . . .and it was really very powerful.

DC: I remember when you were talking to us Nieman Fellows at the Lippmann House – either 1986 or ‘87 — . . .you had just written that novel Selling Out . .

DW: Yeah, that was a Hollywood novel.

DC: . . and you said you were going to that Episcopal monastery in Cambridge, [Society of St. John the Evangelist] and I think you were working on a book, a kind of spiritual memoir.

DW: Yeah, well that was the book the former questioner referred to, called Returning, a Spiritual Journey. And that came out in, I think, ‘85. In fact, I’ll tell you a funny story.

It came out on the Sunday before Christmas in the Sunday New York Times Sunday Magazine, and it was called “Returning to Church.” I came home from church that Sunday and had an answering machine, and I pressed the button in the message, and there was the voice of Kurt Vonnegut and he said, “I forgive you.” So we had a kind of running joke about that. Much later, I saw he had a poem in The New Yorker, and I didn’t know he ever wrote poetry. So I wrote him a card and I said, “I see you’re now a poet. I forgive you.” So that went on.

Maddie Smith: What was the most rewarding experience of your career?

DW: [pause] Oh boy. Well, I think certainly seeing that first piece come out in The Nation was really astounding. . .and I think the other was my first novel because after I wrote a fair amount of journalism and my first book was about Spanish Harlem [Island in the City, 1959] and the publisher with Houghton Mifflin in Boston and I was living in New York. And after that, my dream had always been to write a novel. So I wrote 50 pages of a novel. My agent sent it to him. Because he had published a journalistic book on Spanish Harlem. And we didn’t hear for about a month. And then my agent called. He said, well, Houghton Mifflin wants to pay for you to come to Boston for a day and night and they want to take you to lunch at [?], the fancy restaurant in Boston, and I said to my agent, Is this good or bad? And he said, well, it could be either one. It turned out to be bad. They took me to this fancy lunch and it was not my regular . . editor, it was the head of the company and the managing editor and the publisher, and they said, Dan, we think you’re a wonderful young journalist, but you’re not a novelist.

You know, I later thought, they could’ve just said they didn’t like that 50 pages. But “son, you’re not a novelist,” was really a blow. Luckily, I had some people who really believed in me. In particular, a wonderful poet named May Swenson. And I kept on trying to write a novel and made four or five more false starts, and then finally in 1968 I had written what was a whole issue of the Atlantic on the effect of the Vietnam War on this country, so I had a little money ahead of the game, because that became a book. So I decided, OK, this is it. I’m going to write the novel. It’s now or never. And the novel was called Going All the Way. It became a best seller. Vonnegut reviewed it in Life magazine. It was a great thrill, because that was something I’d always wanted to do. And had been told that I couldn’t do it. So of course I was anxious to send a copy to Houghton Mifflin. And then I learned they had also turned down Julia Child’s book on French cooking. They told [her] that it was too long and that Americans would never be interested in French cooking.

Anyway, I’ve talked about that before — you know, them telling me I’m not a novelist. I always say the moral of that story is, Don’t let anybody else tell you who you are.

DC: I’m wondering, with this room of 14 18- and 19-year-olds. . . How old are you now?

DW: 86. I’m amazed that I am still sort of functioning in all the different ways, which is miraculous. Do a lot of yoga, that’s my advice.

DC: Actually, I just saw something in the New York Times, and it was What would you tell your 18-year-old self, you know, for people much older? And I thought about that, and I won’t say what I would tell myself. But what would you tell yourself?

DW: Well, there was something that I did tell myself. I just happened to see this quote. It was in some kind of library. It was a quote of Abraham Lincoln. And the quote was – and he had obviously given this advice to himself – and he said, “I will study, and get ready, and maybe the chance will come.” So, I’ll never forget when I got that assignment to do the Till trial, I thought of that quote. And I thought I was ready. I remember reading this thing about Michael Jordan talking about being in the zone when you’re playing. And he said, “You know, you can’t make the zone come to you. You have to be ready when it does come.” You know, you have to do all the preparation and get yourself in the condition that you’re ready to go with it.

DC: Well, I hope that’s what four years of a liberal arts education is supposed to be. . . Where did you go to college?

DW: I went to Columbia and it was one of the greatest things. You know, later, when I got the Nieman, at the end of the Nieman year which, as you know, is a year at Harvard, it was the first time I donated to the Columbia alumni fund, because I was so glad I had gone to Columbia and not Harvard. I loved the Nieman program, of course, but I think Harvard is one of the biggest frauds in America. Because, at Columbia, the greatest professors, nationally known professors, taught their own undergraduate courses. Graded their papers. You could walk into their offices any time and see them. At Harvard, the great professors just came out on the stage and gave a lecture and disappeared and then you were taught by graduate students.

Anyway, I was very very happy I went to Columbia because I went to Mark Van Doren, the poet, he was from Illinois, and he had this middle-western accent so I felt at home and all my classmates were from New York and I remember we walked out of Van Doren’s first class and I said, God, Van Doren is great, and one of them said, “Aw, he’s too midwestern.” I said, “Yeah, that’s it.”

DC: You were present at Shaw University when SNCC was formed. You were in Atlanta when the women were trying to figure out how to keep the schools open. Now, looking back on those heady days of the Civil Rights Movement, what do you think about what’s going on now in our country as far as politics and race?

DW: [pause] I think it’s criminal. I hope everybody will read the book Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates. I know I don’t pronounce his first name right. You know, I was a friend of James Baldwin in New York and he told me some things I didn’t understand. I really came to understand them when I read the Coates’ book.

You know, the controversy I had had with Baldwin . . . one night at a dinner, he was talking about his younger sister and how she was 16 and she wanted to be a fashion designer and she was [?] and she was going to suffer, and somebody there said, yeah, well all 16-year-old girls suffer. And I said, yeah, all 16-year-old boys suffer. And [Baldwin] turned to me said, “You don’t understand.” And it was really painful, because I thought I did understand. And I really think I came to understand more reading that Coates book. That in addition to everything else, if you’re black in this country, you have the fear of your body being destroyed anytime. I mean, any policeman, as we’ve now seen on tape many times on TV, can take you out of your car and shoot you or put you jail for almost anything. And as you know we have the greatest mass incarceration of any time in our history and of any place in the world. And what’s happening now is politically . . .well, I don’t need to say it.

You know, some people said I lived through the McCarthy era, was that worse? I said, “No, because we had real. . .we didn’t have Fox News. So we didn’t have an alternative universe of facts. And we didn’t have the social media that allows anybody to, you know, vent their own hate and their own false premises. That’s my speech.

DC: Yeah, well that was awfully good, and we’ll have to end on that. You’ve really given us an amazing 45 minutes. I can’t thank you enough. I’m going to transcribe this and maybe I’ll send you a copy.

DW: Ok, thank you very much. I’m glad to talk to you. . . say hello to Kevin [Finch].