Those ubiquitous traffic accidents called fender-benders can take on an after-life all their own. They send out invisible tendrils that attach, as if by a sticky toxic resin, to body shops, insurance policies, faceless insurance agents, lawyers, police reports, traffic charges, court fees and a Kafkaesque limbo. And that’s just for a white man like me. But this one was the other driver’s fault.

On Nov. 28, at the blinding half-hour when the setting sun rifles out West Howard Avenue in Decatur, Ga., a westbound car turned into the driver’s side of my 2010 Toyota Yaris. I was driving eastward in slow traffic through a green traffic light, the sun at my back. The other car was making a left turn at the little wish-bone jag of Atlanta Avenue that crosses the railroad tracks. I was going slow enough to veer right a little to get around this out-of-its-lane other car, but it kept coming. Like in a slow-motion dream, the other car didn’t decelerate until it plowed along my driver’s side. We both pulled our cars into the conveniently located service station. A police cruiser pulled into the station too, conveniently right behind the other car.

When I saw the two ladies in the other car, I felt a strong impulse to minimize their fault, which was obvious enough and ready to be documented by the female police officer approaching us. The driver was a Black lady in her late 60s. The passenger was her mother, in her 90s. As I learned, they were heading home after early voting in the runoff election for the U.S. Senate, a historic contest between Democratic incumbent Raphael Warnock and Republican challenger Hershel Walker – two larger-than-life figures in our national political drama. I was also heading home after voting. I had voted for Warnock in the runoff, and in fact had been canvassing for him earlier that day. All three of us were wearing “I Secured My Vote” stickers. They voted for Warnock as well, I learned later.

Early voting in DeKalb County was taking up to an hour of waiting in line.

When two cars collide, or any dramatic “accident” happens, one wonders about the preceding minutes and hours that made that event possible. Our waiting in line to vote sacrificed just the amount of time needed for the other driver to be going home into a blinding sunset exactly when I was driving by.

I told her I didn’t want to cause her any trouble, since there seemed to be little damage done to either car, and my humble Yaris could live with the scars. I was thinking of how a little accident like this could be a nightmare for anyone at fault (and I could imagine being at fault in some other accident, some other day). For her, it could be worse. I knew that for a Black person in a 20-year-old car, a woman taking care of her elderly mother, those entanglements with insurance, court costs and traffic offenses could be ruinous. She must’ve sensed my dilemma, because she offered this bit of reassurance.

“Everything happens for a reason,” she told me.

The police officer, young, white and with a subdued air of self-confidence, asked if I wanted her to write up a report – which would be a charge against the woman of failure to yield while turning left. The fine and court fee for this charge, we would learn later, would be $223.25. Repairing my car would be more, if I took it to a body shop. I hesitated.

I could let the whole thing drop. But life experience told me this needed to be on the public record. Years ago, I barely saved four of us in a Camry I was driving when an 18-wheeler pushed us halfway out of our lane on an interstate in Virginia. I took pictures and got the trembling Russian driver’s name. But it was near midnight and bitter cold, so we didn’t wait in that dangerous breakdown lane for police to arrive. Months later, I learned my insurance company had settled with the trucking company over its claim that the accident was my fault. There was no police report to contradict the claim. As a former journalist, too, I want facts to be verified by a public record.

Yes, I said, write it up, I told the officer. But as I told the woman driving the other car, I will testify in your favor. She said she knew she would be charged and need to go to court, but she didn’t seem to blame me for requesting the write-up. It was her fault, she said. The sun had blinded her and she didn’t see my car.

I am not unaware of the difference between a white man like me going to court, for whatever reason, and a black woman going to court. Having covered trials and court filings as a news reporter, I view the criminal justice system as a flawed but essential foundation of God-given rights. But I’ve studied the history. When the Swedish sociologist Gunner Myrdal researched race in the South for An American Dilemma (1944), he found that “Negroes” never enjoyed the trust that whites had in the courts. They were terrified. “Whites were the judges, the jurors, the bailiffs, the court clerks, the stenographers, the arresting officers, and the jailers,” as Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff wrote in The Race Beat. “Only the instruments of execution. . .were desegregated.”

This split-screen reality of the courts left a generational trauma for Blacks, like a fear of big dogs or deep water. Young Black men who already had run-ins with the law would instinctively run when cops told them to stop and submit. That’s what happened in Atlanta in 1966 when a white police officer stopped Harold Louis Prather to question him about a carjacking. He ran, and the policeman shot him twice in the hip and side. Bleeding, the youth collapsed on his mother’s porch and blamed the cop. By the end of the day, the Summerhill neighborhood was in full riot, with Stokely Carmichael and Mayor Ivan Allen playing historic roles.

In January this year, what happened in Memphis to the 29-year-old Black photographer Tyre Nichols seemed similar. The cops, this time, were Black, and the FedEx worker apparently had no police record to prompt him to run for it. But after an initial “confrontation,” he did run. And, like Prather in Atlanta, he ran to his mother’s house, calling “mom” as the officers beat him mercilessly. He died three days later.

Our hearing at Decatur Municipal Court was scheduled for Jan. 19, a weekday, at 6 p.m. This may have been an inconvenient time for a judge and other city workers to hold court, but it was good to accommodate people who need to work during the day. In the bright, modern courtroom sat about a dozen adults, all of them Black, waiting respectfully. Sitting closest to the door was the driver of the car that hit me. We greeted and I sat beside her to join the wait. A middle-aged white man in a coat and tie came in to sit at a desk near the front. I would learn that this was City Solicitor Larry Steele.

There’s something unnerving about being the only white person in a courtroom full of black defendants and their kin waiting for justice, when in comes a white Solicitor. Of course he represents one side of this evolved English system we have, with our rights from the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Amendments of the Constitution guaranteeing presumption of innocence, equality before the law and all that. In terms of the law, his race was irrelevant. I knew that.

But it was a relief to me when “All rise” was called and the judge took her place in the seat above all, Municipal Court Chief Judge Rhathelian Stroud, a Black woman. The defendants came before her when called. She was serious, but reasonable. One man who looked to be in his 60s couldn’t pay his fine and court fees, so he was given 13 hours of community service to work off the $200 debt, instead of jail time. He was sent away with instructions to get his community service orders.

Later, I learned something about Judge Stroud from reports in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution from December 2017. At that time, another judge with Decatur Municipal Court, Lindsay Jones, had sentenced a woman to spend two nights in jail – starting with the night of her 20th wedding anniversary – for contempt of court. Judge Jones attacked the woman’s account of a minor traffic infraction by playing a video of her car in an intersection under a red light, then jailed her for “perjury.”

The woman, her husband and her lawyer, all of them Black, were quoted in news accounts calling this punishment outrageous and embarrassing.

“This is what he does,” the woman’s husband told WSB-TV. “If you dispute a ticket in this court, you’re going to jail.” The attorney added: “We have to have a day of reckoning over this. This can’t continue to happen.”

Chief Judge Stroud, who was in effect Judge Jones’s boss, learned of the penalty and met with Jones, who is an adjunct law professor at Emory University with a long history of advocating for civil rights and multicultural understanding. According to an email Judge Stroud sent to the City Manager, she listened to Jones explain what he did. She shared her “concerns and subsequent expectations” with him, and Jones resigned. The woman was released from jail after only one night.

This was the same Judge Stroud who called our names to come forth. The woman driver pleaded “not guilty,” which marked the start of her bench trial. The Solicitor and the female officer were standing by a lectern on the left side. The driver who hit my car was standing at a lectern on the right. I was told to stand on the left with the other two. That would put the only three white people present together.

“Your Honor,” I said from the Solicitor’s side. “I’m a friendly witness.”

Well, the judge said, you can go over to be with the Defendant, which I did. We were sworn in.

Solicitor Steele presented his case. The officer gave her report of the accident. The Defendant acknowledged that the officer’s account was accurate, but that she was blinded by the sun, and “Mr. Cumming and I talked and he said. . .”

“Objection, your Honor,” said Steele. This would’ve been hearsay. So I was called on for my testimony. I explained that I considered not pressing charges, but did so only to have a record on what happened. There was little damage and no repair costs, I said. The judge asked if I had reported it to my insurance company. No, I hadn’t.

The solicitor did not seem happy with how things were going. He pointed out that the Defendant had broken the law. I recognized that he was just doing his job, protecting the safety of the public. From his perspective, I was getting in the way. I had no business being here unless it was on his side, since the “victim” in a crime like this is really the State, not me.

Judge Stroud was ready to pass judgment. Guilty as charged. Then the judge suspended the entire $223.25 penalty.

We left, relieved.

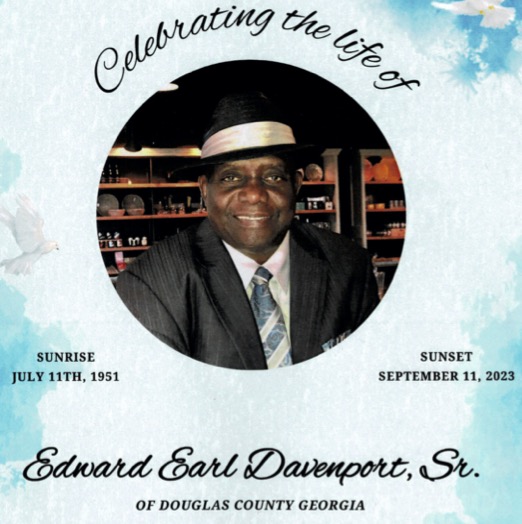

A few weeks later, I received a card from the Defendant, a woman who had retired after more than 30 years working in cancer wards at Emory University Hospital and the adjacent Children’s Hospital of Atlanta. The card was a Hallmark thank-you with generic printed words “for everything you have done. . . for everything you have given. . .”

She also wrote in her own hand: “Thank you for your help. . . It’s good to know there are still some good people around.” Everything happens for a reason, but my reason was not to be called good. It was, in part, to see the accident from her perspective, illuminated, in a sense, by the light of the day’s sun.